Senior Care: Institutional Infections

Healthcare-Associate d Infections

d Infections

Perhaps, the reasons and ultimately the deciding factors to consider Home Care Services for your loved one are too many to mention. I could not agree more that its the best decision, for another reason that you may not be aware.

The difficult decision to place a loved one in an institutional setting is intended on keeping them safe, healthy and well taken care of. There are some great institutions whose primary goals and objectives are just that… and do a great job at it. Unfortunately, they do not have the capacity to protect your loved one from the increased probability of contracting infections that are normally present in the very nature of an institutional setting. Some of these infections are highly contagious, nasty and some are even drug resistant. When they’re contracted there’s no simple method of eradication and the elderly are not only susceptible to contracting them, but can even die from it. Below are some details from the Public Health Canada.

The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada, 2013 Infectious Disease—The Never-ending Threat.

Below I will share some of the relevant details as it pertains to infection control and seniors.

Highlights:

- More than 200,000 patients get infections every year while receiving healthcare in Canada; more than 8,000 of these patients die as a result.

- Mortality rates attributable to Clostridium difficile infection have more than tripled in Canada since 1997.

- The healthcare-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection rate increased more than 1,000% from 1995 to 2009.

- About 80% of common infections are spread by healthcare workers, patients and visitors.

- Proper hand hygiene can significantly reduce the spread of infection.

- Best practices in preventing infection can reduce the risk of some infections to close to zero.

The report goes on to say that – Contracting an infection while in a healthcare setting challenges the basic idea that healthcare is meant to make people well. Hospitals, long-term care facilities, clinics and home care services are meant to help people get better. Yet it is estimated that more than 200,000 Canadians acquire a healthcare-associated infection (HAI) each year and that 8,000 of them die as a result. Although definitive numbers are not available, it appears that these numbers are rising.

The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that HAIs (also known as nosocomial infections) are universal, affecting healthcare systems in every country.

However, noting that Canada is not alone does not make it less of a problem or any more acceptable. More must be done to keep Canadians safe while they seek treatment and care.

A healthcare-associated infection (HAI) is an infection that a patient contracts (or acquires) in a setting where healthcare is delivered (e.g. a hospital) or in an institution (e.g. a long-term care facility) or in a home care arrangement. The infection was neither present nor developing at the time the individual was admitted (or started treatment).

Some of the HAIs monitored by the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP) include:

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections;

- Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) infections;

- Clostridium difficile (C. difficile);

- Surgical site infections (SSI); and

- Central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infections (CVC-BSI).

Preventing HAIs involves the right engineering and the right equipment; attention to hygiene; training of healthcare providers and staff; and the cooperation and help of patients and their families and friends. Washing hands, cleaning environments and sterilizing instruments are the best ways to prevent HAIs.

However, following best practices is not always simple. It involves many people and increasing awareness in a complex environment. Educating and encouraging healthcare workers, patients and visitors to wash their hands at the right time and consistently perform other hygiene practices is one challenge. Others include the ever-changing characteristics of infectious agents and the increasing risk of infection associated with advances in medical care and increasingly vulnerable patients.

Becoming infected

People become infected with bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites when these micro-organisms spread through the air, through direct or indirect contact or when infected blood or body fluids enter the body (e.g. the bloodstream).

The risk of infection is higher in places where people gather, and the impact is magnified in hospitals and long-term care facilities because patients are already ill and at particular risk of infection due to medical interventions and “hands-on” care. About 8% of children and 10% of adults in Canadian hospitals have an HAI at any given time.

The severity is greatest among those who are elderly, very young, have weakened immune systems or have one or more chronic conditions.

Of greatest concern are the bacteria that are resistant to multiple types of antibiotics. More than 50% of HAIs are caused by bacteria that are resistant to at least one type of antibiotic.

Some infectious agents can spread easily from people who are infected to those who are not. They can also spread from healthy individuals who may carry the agent but do not develop clinical infections or know they are sick. Infection can easily spread from patient to patient through the hands of healthcare workers during treatment or personal care or by touching contaminated shared surfaces, such as bathrooms, toilets or equipment. Even the simple act of holding a loved one’s hand can risk spreading infection if hands haven’t been correctly washed.

An infected individual is one in whom infectious agents have developed to the point where the person gets ill and shows symptoms such as fever and high white blood cell count. An infected person may transmit infectious agents to another person through touch (direct to another person or indirect touching of the same object). However, not all individuals exposed to the infectious agent become infected and sick. Instead, they may become colonized.

Since most colonized individuals have no symptoms, they are unaware they are carrying the infectious agents. As a result, everyone—not just those who are sick—must be vigilant about hygiene and handwashing to protect others.

For some bacteria and viruses the number of colonized people is much higher than the number of infected people (i.e. who are sick). The relationship between the number colonized and the number infected is often referred to as the iceberg effect. The smallest part of the iceberg—the tip visible above the water—represents those who are infected and have symptoms. The largest portion of the iceberg—underwater and mostly invisible—represents the number of colonized people with no symptoms.

The key message here is, that which is visible is not representative of all that is present and we need to be concerned with what is not always visible. While direct person-to-person touch is the primary pathway, the healthcare environment itself can be a route of transmission. Bacteria can exist on many objects in the patient environment (e.g. bedrails, telephones, call buttons, taps, door handles, mattresses, chairs). Some of those bacterial agents can survive for a long time—in some cases for many weeks and even months.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) are two of the most well-known bacteria that are able to adapt and survive in the healthcare environment long enough to cause infection.

Clostridium difficile (C-Diff):

C. difficile is not a new bacterium. First identified in the 1930s, it was recognized as a cause of human illness in 1978.

Within the last five years, C. difficile has earned much public attention as a difficult-to-control superbug that attacks vulnerable patients, particularly the elderly, and undermines the safety of healthcare institutions.

The bacteria are found in feces and causes mild to severe diarrhea as well as other serious intestinal conditions, including life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis, bowel perforation and sepsis.

C. difficile infection (CDI) is the most frequent cause of infectious diarrhea in hospitals and long-term care facilities in Canada.

In hospitals reporting to the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP), the incidence of CDI in the first nine months of 2011 was 4.5 cases per 1,000 patient hospital admissions.

Although the incidence of CDI has remained fairly steady in recent years, the severity seems to be increasing. The mortality rate attributable to CDI in Canadian hospitals more than tripled over the last decade and a half, from 1.5% of deaths among CDI patients in 1997 to 5.4% in 2010.

The bacteria can be spread by touching contaminated feces and then a surface object and/or an individual. Eventually, the bacteria can reach the mouth or nose as a result of touching one’s face or eating.

Some populations, particularly seniors and those who are immune-compromised, are more vulnerable to infection.

C. difficile is not a significant risk for healthy people; however, they can still be colonized, potentially passing on the bacteria to others who may become infected.

Research on object contamination shows that as levels of environmental contamination increase, so does the prevalence of C. difficile transmitted between healthcare workers and from them to patients.

This specialized bacterium is very difficult to remove. It creates spores that are resistant to many of the usual cleaning and disinfection practices. The spores can survive for up to 5 months on surfaces such as tables, medical equipment and other objects, making hygiene critically important in hospitals and healthcare institutions.

C. difficile is a particular problem for people already on antibiotics. Antibiotics kill many of the normal ‘good’ bowel bacteria, allowing C. difficile to multiply and produce the toxins that damage the bowel and cause diarrhea.

Simple acts can help reduce the risks of CDI. For example, proper hand hygiene can make a big difference. Since the spores are resistant to alcohol, washing hands with soap and water is recommended over alcohol hand rubs in a healthcare facilities experiencing outbreaks of C. difficile.

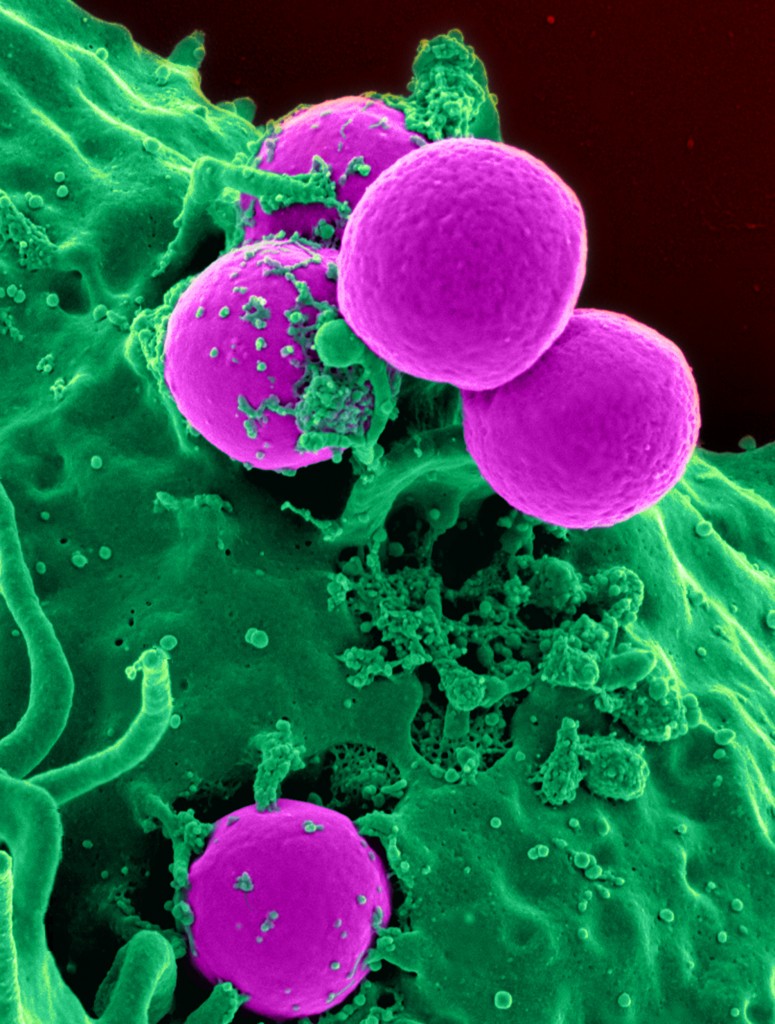

Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA):

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a drug-resistant form of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)—the most common cause of serious hospital-acquired infections. S. aureus spreads primarily through direct skin-to-skin contact as well as indirectly, as when people share personal items such as towels, razors and needles. If this bacterium enters the body it can cause infections in many areas including the skin, bones, blood and vital organs such as the lungs and the heart. Many people have S. aureus on their skin at any given time and approximately 30% of people are colonized with S. aureus in their nose.

For healthy individuals, this does not pose a threat; however, they could spread the bacteria by touch to other people. This is particularly difficult to control in healthcare settings where healthcare workers need to touch patients to assess, treat and help them. In addition, visitors often touch a patient to greet or comfort them.

Of particular concern in healthcare situations are MRSA infections as these are generally multidrug-resistant. In the early 1940s, penicillin was completely effective in treating S. aureus. However, after this antibiotic became widely used, the micro-organism quickly adapted and became penicillin-resistant. In the early 1960s, the antibiotic methicillin was introduced and shortly after that MRSA emerged.

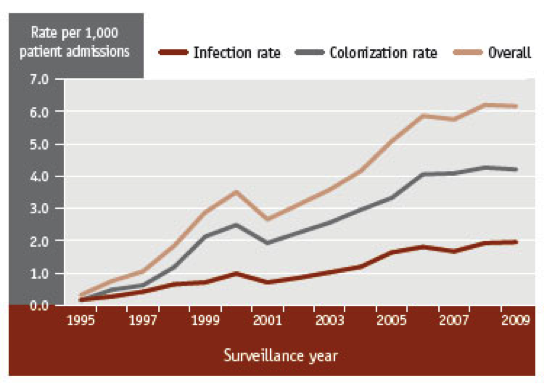

Healthcare-associated MRSA rates per 1,000 patient admissions from 1995 to 2009, Canada: Rates of healthcare-associated MRSA infection and colonization have been steadily increasing for more than a decade.

The combined, overall rate went from less than 1 case per 1,000 patient admissions in 1995 to more than 6 cases in 2009. The infection rate increased by more than 1,000%, from 0.17 cases per 1,000 patient admissions in 1995 to 1.96 cases in 2009. The increase in the colonization rate was even larger, with the number of colonized cases per 1,000 patient admissions climbing from 0.15 in 1995 to 4.21 in 2009.

Recognizing the global need for infection control, WHO launched the first Global Patient Safety Challenge in 2005—an international campaign to encourage member states to reduce the risk of infection in healthcare settings. The “Clean Care is Safer Care” campaign includes several components: clean products, clean practices, clean equipment and clean environment, all within the overall goal of implementing WHO hand hygiene recommendations.

Canada joined the Global Patient Safety Challenge in 2006 and later launched the Canadian Patient Safety Institute’s (CPSI) Stop! Clean Your Hands program. This program is part of Canada’s Hand Hygiene Challenge, which is meant to improve hand hygiene practices and compliance in healthcare settings.

Hand hygiene: It’s clear that clean, healthy hands equals better health. Proper hand hygiene—washing hands with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand rubs—is the single best way of preventing HAIs.Even small improvements in hand hygiene result in large benefits: an increase in adherence to hand hygiene by only 20% has been shown to reduce the rate of HAIs by 40%.

Even though infection control today has new challenges, such as antibiotic resistance, the principles of hand hygiene remain key to preventing infection. For example, the use of regular soap and water, rather than antimicrobial soaps, is sufficient. In fact, antimicrobial soaps may contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance. When hands are not visibly soiled or soap and water are not readily available, alcohol-based hand rubs should be used.

Despite public health messages about the importance of washing hands to reduce the spread of infection, handwashing is not always done effectively. This could be because people establish hand hygiene patterns in childhood. Old habits are hard to break—changes in practice can be difficult and slow even among some healthcare professionals.

Everyone needs to learn and practice the correct technique for hand washing:

- Remove all jewellery and rinse hands with warm running water

- Use a small amount of liquid soap in the palm of your hands and rub your hands together for about 20 seconds to form a lather that covers your entire hands including the palms, the backs, the backs of the thumbs, the fingertips and between the fingers

- Rinse hands well for about 10 seconds and then dry completely. Try not to touch faucets and other items with clean hands

It is never too early to learn the basics of washing hands. Parents, teachers and childcare workers can teach children the importance of handwashing as well as how to do it correctly. The amount of time it takes children to soap their hands thoroughly is the same as the amount of time it takes to sing a nursery rhyme such as “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.”

Patients can also make a difference and improve hand hygiene practices among healthcare workers and visitors by simply asking if they have cleaned their hands or requesting that they do so. However, while most patients want to be involved in improving hygiene, many say that they are reluctant to ask questions in case they become a nuisance to their healthcare team.

Better efforts are needed to make patients and their advocates feel comfortable in speaking up for their own safety and to encourage them to be vigilant in healthcare settings.

Many healthcare settings now use external cleaning services. In these situations, it is also essential that proper policies and procedures are followed. After cleaning and disinfection of the environments in healthcare settings is carried out, there are no national standards in Canada to measure how clean things are. Instead, the level of cleanliness is assessed by how clean things look. Researchers in the United Kingdom found that 90% of the wards that looked clean still contained unacceptable numbers of micro-organisms.

Monitoring infection

Most HAIs are preventable. As many as 70% of some types of HAIs could reasonably be prevented if infection prevention and control strategies are followed. However, just because some type of monitoring occurs does not mean that it is effective in preventing and controlling HAIs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States carried out the Study on the Efficacy of Nosocomial Infection Control (SENIC) project to identify the most effective approaches to infection surveillance, prevention and control.

A survey of Canadian hospitals with more than 80 beds reported in 2008 that hospitals carried out, on average, only two-thirds (68%) of the recommended surveillance activities based on SENIC project findings and only 64% of the recommended infection control activities. In addition, only 23% had the recommended number of infection control professionals on staff.

Mandatory standards, monitoring and public reporting are necessary to understand and tackle HAIs. Some current practices are inconsistent and uncoordinated, and more could be done to improve monitoring, addressing and reporting of HAIs in Canada.

HAIs complicate the lives of Canadians when they are at their most vulnerable, resulting in longer illnesses and greater risk of death. They can impact people even after they are discharged from healthcare facilities. What’s more, the longer patients remain infectious, the longer they can spread infectious agents to others.

There is no doubt that Canadian Institutions understand the magnitude of this problem. However, there’s an inherent complexities within institutions that make it difficult to implement effective and sustainable infection control practices.

While Home Care may not eliminate infections completely, it certainly removes the environmental risk and conditions that contribute to contracting infections. Home Care is a controlled environment and much easier to implement effective & sustainable practices to safeguard your loved one against infections.

Please contact us today, to discuss any challenges you may be facing and how our services can help you remain independent, protected, safe, and in you home / community.

You got questions, we have answers: (905) 785-2341 or email us at